Developments in China’s Climate Finance Journey

Chinese policymakers are threading the policy needle between short-term economic interests and long-term climate commitments. Threats to economic growth continue - the Fall 2021 energy crisis, the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and the zero-Covid policy. Meantime, China understands the long-term economic and geopolitical advantages to pushing forward its domestic climate agenda and steering the global narrative.

This briefing summarizes China’s climate policy developments, highlights its new experimentation in climate finance, identifies challenges in implementation, and suggests what to expect from China at COP27.

At a glance

-

President Xi Jinping has made ambitious commitments for China to peak carbon emissions before 2030 and to reach carbon neutrality before 2060.

-

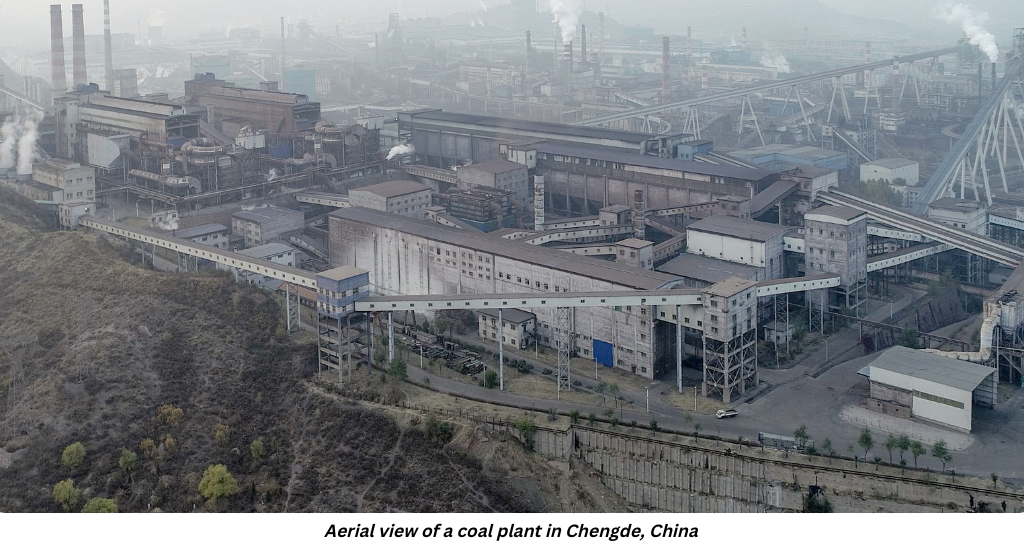

Achieving these goals is complicated by the global energy crisis, slowing economies post-Covid and coal usage rising as China’s primary energy source.

-

While China remains committed to overcoming these challenges and achieving its goals, finding the necessary financing to transition to carbon neutrality also remains a major obstacle.

-

To channel more funding to climate mitigation and adaptation efforts, China announced in August 2022 that 23 climate finance pilots were being implemented across 19 provinces. The hope is that, if successful, the pilot projects can be expanded nationwide.

China climate policy past and present

Though China was one of the original signatories to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992, climate efforts have long been secondary to China’s economic agenda, which has focused almost exclusively on GDP growth.

For the last decade, however, under President Xi Jinping’s leadership, climate policy has gradually risen in priority. Most significantly, in September 2020, Xi announced at the UN General Assembly that China would adopt more aggressive climate policy with dual carbon targets:

-

Peak CO2 emissions before 2030

-

Carbon neutrality before 2060.

China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP 2021-2025) in March 2021 also marked a milestone when, for the first time, it contained no GDP growth target and instead emphasized sustainable, “high-quality development.” It also set out two binding climate targets for 2025 (compared to 2020 levels):

-

To reduce CO2 emissions (per unit GDP) by 18%

-

To reduce energy consumption (per unit GDP) by 13.5%.

How China climate policy works

For China to meet these challenges, it will require political will, financing and direction from the center to ensure transformation of China’s most polluting industries.

Beijing has made the carbon transition a priority, but implementation is challenged by the recent leadership changes and the global slowdown exacerbated by Covid, combined with rising energy prices. To create a structure for change, climate policy has its own hierarchy to implement decarbonization throughout the complex policy environment. This hierarchy from central to provincial to municipal governments – called “1+N” – features a central guidance document (the “1”) with key climate and energy targets, and then supplemental plans (the “N’s”) that filter down through the system, addressing institutional mechanisms, financing, and issue- or industry-specific guidance.

Already, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), China’s macro planner, has confirmed 11 “1+N” plans are in the works, including energy, transportation, petroleum and petrochemicals, natural gas, agriculture and rural areas, and building materials.

Once developed, these new policies will be tested locally, which allows Beijing to experiment with different policies before applying the best practices nationwide – a policy norm that originated during China’s experimental Reform and Opening Up.

China's climate finance experiment

Financing is key to climate action success and Special Envoy on Climate Change, XIE Zhenhua, estimates China will need RMB 136 trillion (USD 19.5 trillion) to achieve its climate goal on carbon neutrality.

In the weeks following Xi’s dual carbon targets announcement at UNGA, five top-level ministries/regulators jointly released “Guidance on promoting investment and financing to address climate change” to encourage capital investment in climate mitigation and adaptation efforts. And in December 2021, as one such task under that guidance, nine central government agencies released the “Climate Investment and Finance Pilot Work Plan,” which aims to channel more funds into climate mitigation and adaptation projects at the local level, including:

-

Optimizing the energy mix

-

Developing non-fossil energy

-

Controlling greenhouse emissions from industry, agriculture and waste disposal

-

Expanding carbon sinks, such as forest and grassland

-

Strengthening adaptation capacity in agriculture, water and disaster management

-

Accelerating infrastructure development

-

Establishing carbon accounting and information disclosure systems

-

Developing a national carbon market

-

Developing carbon finance products

In August 2022, Beijing began experimenting with these climate finance policies on the ground with its first batch of 23 pilots across 19 provinces. The pilot sites vary widely in terms of industry, energy structures, economic scale and population size, but fit roughly into three distinct categories:

-

Areas with strong economic foundations and leeway to risk trial and error, including Shanghai’s Pudong New District, Beijing’s Tongzhou, and Shenzhen’s Futian District.

-

Areas heavily dependent on traditional industry or natural resources, such as Baotou in Inner Mongolia, Sanming in Fujian, and Lanzhou in Gansu.

-

National-level new zones tasked as models of innovative development that have capabilities and demand for climate finance, including Liangjiang New Area of Chongqing and Tianfu New Area of Sichuan Province.

With policy and funding incentives from the local government, these pilots will serve as on-the-ground laboratories for high-level climate policy. Best practices among the pilots will be scaled nationally.

Challenges facing climate finance

The success of these pilots will face considerable challenges over the next three to five years, including the growing development of climate finance, creation of a consistent green taxonomy, enforcement mechanisms for implementation supervision mechanism, and the lack of climate and biodiversity disclosure on a consistent basis. China also needs to diversify climate finance participants so that the market is not comprised of strictly bank loans. For mitigation and adaptation solutions to gain traction, there are two immediate challenges that need to be overcome: access to capital and collaborative governance.

Lack of capital is an important obstacle to climate finance solutions.

In China, the government will only be able to provide about 10% of required capital. To attract more private capital investment to climate solutions, China must build a comprehensive climate finance system, including creation of platforms to connect projects with capital investment, carbon accounting and climate information disclosure requirements. The government is also considering incentive programs for other sectors, much like they have used to promote EVs.

-

According to the Asset Management Association of China, over 1,000 green funds have been registered in China as of the end of 2021. Opportunities are growing but still fall far short of meeting market needs.

Collaborative governance may also hinder climate finance efforts.

The Ministry of Ecological Environment (MEE) is the official lead when it comes to environmental policy, but the reality is that they are one of the weakest ministries in the system. Instead, the powerful National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) – tasked with developing macroeconomic policy – is really driving the actions on climate, which suggests environmental policy, in practice, remains subservient to China’s economic interests. In addition to the policy making challenges, neither of these institutions, MEE or NDRC are experienced or act as regulators for financial markets, yet they are driving parts of climate finance policy. The spot market under China’s National Carbon Exchange, for example, is MEE’s responsibility. Until these governance issues are clarified, progress will be bumpy towards creating an effective climate policy strategy.

What to watch at COP27

What are China’s goals

Egypt is hosting COP27 so its agenda will likely feature climate adaptation, climate financing, and international mechanisms mitigating challenges in the Global South. China has positioned itself as a leader of emerging markets, so China is expected to prioritize support for programs and policies focused on providing financing to help emerging markets meet their climate goals.

Who is attending From China

China‘s official delegation is led by ZHAO Yingmin, Vice Minister of MEE, who is likely to replace XIE Zhenhua as China’s Special Climate Envoy. Delegation members include XIE Zhenhua, Chinese Climate Special Envoy; LI Gao, Director General of Climate Change Department of MEE; QI Dahai, Climate Negotiation Representative and Deputy Director General of Law and Treaty Department from Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA); together with representatives from National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Commerce, and the Ministry of Agriculture.

Other officials and scholars from major Chinese academic institutions will also join the delegation, including LI Zhen, Executive Vice President of Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development, Tsinghua University (ICCSD); WANG Yi, Vice President of Institute of Science of Development, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CASIC); and WANG Zhongying, DG of Energy Research Institute, NDRC (ERI).